Back

The genre of cognitive estrangement and novum, alternative past and future, critical thinking, utopia and dystopia, speculation and exploration, encounter with the Other, as well as technology, apocalypse, extrapolation, paranoia and futurism is in the focus of Animafest 2023’s theme programme. Although some SF theorists exclude Jules Verne, beginning its modern history with H.G. Wells, an overview of cinematic science fiction usually begins with Verne’s “adaptor”, the magical innovator Georges Méliès and his A Trip to the Moon (Voyage dans la Lune, 1902), which, after all, relied on the works of both writers. A Trip to the Moon is not considered a purely animated film, but its intensive use of stop-trick, the introduction of drawn elements into the scene, manual colouring of the film tape and theatrical mise-en-scene make it to a large extent close to animation, and therefore the artistic director of Animafest, Daniel Šuljić, included it in the theme programme of this year’s festival (unit “SF 2: The World of Tomorrow”). Both for the highly stylised feature-length origins of cinematic SF Aelita and Metropolis, or at least for their expressively illustrated backgrounds and effect, and for both the early golden periods of the genre in the 1930s and 1950s, with their lost worlds, utopian projections, universes, monsters and bombs, not only the artistic genetic link with the animated film is valid, but also the one that results from the abundant use of stop-motion of puppets and scale models.

Science fiction in the past of short animated film appears, however, sporadically and very rarely as a constant in some author’s oeuvre, or a permanent expression of a school or production company. The history of short-length animated SF has therefore not yet been thoroughly covered, so the theme programme of Animafest 2023 in nine units is structured topologically instead of chronologically. The position of sci-fi in short animation is also outlined to a certain extent in the production of Zagreb film, active on the border between East and West since the second half of the 1950s and has contributed to the animated revolution of global proportions – to the authors of the Zagreb School of science fiction, parables were only occasionally of socio-critical use. This ethos, however, will be updated again in the 21st century, so “SF 6” as a whole, dedicated to a selection of SF films from the 70-year history of Zagreb Film (Tuesday, June 6, SC Cinema, 10 p.m.), includes classics such as Vukotić’s Cow on the Moon and Grgić’s Visit from Space joined with the more recent works by Kukić (Vremeplov), Pisačić (Choban) and Belić (Flimflam).

The golden age of short animated science fiction is actually right now. In the last fifteen years, Animafest has presented dozens of excellent SFs in its competitions, among which we could single out those who are primarily interested in technology – both AI and other ‘software’ – and gather them into a unit “SF 1: The Future is Now” (Tuesday, June 6, &TD Theatre, 8 p.m. and Friday, June 9, SC Cinema, 3:30 p.m.). For example, Sean Buckelew, independently or as part of the collective Late Night Club, has appeared several times at the Zagreb festival since 2017 and the notable Lovestreams about encounters in virtual space, and his new film Drone, which is screened in this unit, is driven by the already established motif of the renegade spacecraft (cf. e.g. Vladislav Knežević’s A.D.A.M.). In the film Algodreams, Vladimir Todorović mentions AI software with which he willingly shares authorship, and Mitch McGlocklin’s pointillist-striped, neo-noir autobiographical etude in cyberspace Forever focuses on the topic of the relationship between advanced technology and human experience, that is, infamous algorithms that collect and analyse our private data. Realised in LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), Forever attributes to AI, however, the positive values of a guarantor of eternity and a companion in an alienated world. All My Scars Vanish in the Wind (dir. Angélica Restrepo, Carlos Velandia) uses photogrammetry, and the beautiful experimental Hysteresis by Robert Seidel, an artist particularly interested in nonlinear systems and bifurcations, also uses AI and digital compositing.

In “SF 2: The World of Tomorrow” (Thursday 6/8, &TD Theatre, 8 p.m. and Friday 6/9, Tuškanac, 5:30 p.m.) Trip to the Moon is also in the company of films less than a quarter of a century old. Among them are animation big names like Don Hertzfeldt’s eponymous World of Tomorrow – an Oscar-nominated Sundance winner and the starting point for a now three-part series that takes on a number of sci-fi tropes like cloning, time travel and melancholy, building an army of fans with a unique avant-garde-simple style and combination of humour and fatalism, philosophy and hope. There is also Phil Mulloy, a giant of satire and the grotesque, the prince of animanarchy and a fierce social critic who in his own way captures the war between Earth and the planet Zog (Intolerance II: The Invasion). Evert de Beijer’s Car Craze is also a work of raw animation – an environmental parable about parasitic body-stealing cars. Finally, Dmytro Lisenbart’s Ukrainian film of more classical beauty, Unnecessary Things, is based on Robert Sheckley’s short story about a near future where a lonely robot takes a human as a pet.

The contemporary flourishing of short SF does not mean, however, that some classic directors have not tried their hand at it. The recently deceased Belgian master, Animafest laureate Raoul Servais, did it back in 1971 with Operation X-70, an animation of copperplates telling the story of experimental nerve gas bombs, which will be screened in “SF 3: Disasters” (Thursday 6/8, Tuškanac, 5:30 p.m. and Friday 9 June, &TD Theatre, 8 p.m.). Operation X-70 is here put in context with more recent works of a similar theme, in which the modes of psychological SF and the motifs of astronauts prevail. Tomasz Popakul’s Black depicts them trapped on a space station in Earth’s orbit due to an atomic war, Marina Belikova’s The Astronaut’s Journal, based on Stanisław Lem, combines internal, introspective, humane and psychological research with the outer-spatial one, in the Turkish film Avarya by Gökalp Gönen a man is trapped with a robot on a spaceship in search of a habitable planet, and in 909 Depart of the Uber Eck studio we fly through the space station in first person and become aware of another end of the Earth. Kevin Iglesias Rodríguez and Pedro Rivero’s pandemic allegory The Days That (Never) Were is based on the premise of Jupiter occupying the Moon’s position, and Jérémy Clapin’s Skhizein is another psychological, highly original SF about a man that, due to a meteorite impact, experiences a “spatial shift” of 91 centimetres. It is the film that plastically points out the advantages of animated film in the presentation of “impossible” phenomena.

Chris Marker’s famous short photo-film SF La Jetée (1962) is less often mentioned in the context of an animated film, but the French New Wave artist made a stop-motion, collage-pixilation film Astronauts awarded in Venice and Oberhausen as early as 1959 with Walerian Borowczyk (whose birth centenary Animafest 2023 also marks in the Poland in Focus program). Astronauts are featured in “SF 4: Science Friction – Collage in Space” (Wednesday 6/7, &TD Theatre, 8pm and Friday 6/9, SC Cinema, 1pm) designed by Ottawa Festival Artistic Director Chris Robinson, naming it after the film Science Friction (1959) by the American legend of experimental stop animation Stan VanDerBeek, which, understandably, can also be seen in this block. It is interesting to note that the fruitful, albeit insufficiently thematised, historical triangle of experimental and animated film and science fiction, which is covered by this unit, has one of its most important contemporary expressions in the works of Dalibor Barić, undoubtedly the most important Croatian SF film author today, who designed the illustration and trailer of Animafest 2023. Dalibor Barić is represented in the unit “SF 4” by the found footage film Marienbad First Aid Kit (2013).

In the block “SF 4” you can also see the Hungarian Moon Flight (1975) by Sándor Reisenbüchler – a work from the famous Pannonia Film, a studio that once managed to realise the feature-length Moebius and Laloux’s The Masters of Time (1982) in addition to the works of Jankovics, Dargay and others. Along with newer films from Germany, Norway, Switzerland, Belgium and Hungary, the older Polish film Cockroach. Blatta orientalis by Zdzisława Kudła (1987) is shown in the block “SF 5: Speculative Animation – Return to the Post-Apocalypse” (Thursday 6/8, SC Cinema, 10 pm and Saturday 6/10, &TD Theatre, 8 p.m.) curated by the historian and animation theorist Olga Bobrowska. Science fiction creativity in Eastern Europe in the second half of the 20th century was exceptional, among other things, due to the fundamentally utopian foundations of the social system, but it is often glossed over in Western histories of the genre.

In Romania, Mircea Toia, Călin Cazan and Victor Antonescu also tried their hand at the feature form with Space Mission ‘Delta’ (1984), the restored version of which Animafest will show in “SF 9” (Tuškanac, Wednesday 6/7, 5:30 p.m.). It’s a film about an AI taking over a spaceship on an intergalactic mission, of episodic structure and seductive classic appearances. The Poles, in co-production with France, embarked on the feature SF with Chronopolis (1982) by Piotr Kamler (“SF 8”, Tuškanac, Tuesday 6 June, 17:30), which takes place in a city whose immortal inhabitants are freed from the boredom of eternal existence by devoting themselves to the production of time. A non-verbal spectacle of exceptional and inspiring stop-motion imagery achieved with complex materials and shadow, Chronopolis is a philosophical meditation on the nature of time. Kamler, who mostly worked alone in his avant-garde films, at the same time regularly collaborated with the most important electronic musicians of his time – on Chronopolis with Luca Ferrari.

Feature-length animated SF appeared in Western and Eastern Europe in the 1970s and 1980s, often in close connection with the tectonic shifts of art comics and the new wave of surrealism. Métal hurlant magazine will receive Gerald Potterton’s Heavy Metal (1981), and Moebius himself will collaborate with Rene Laloux on The Masters of Time in Hungary. Back in 1973, Laloux made perhaps the crucial feature-length animated SF Fantastic / Wild Planet with Roland Topor, a French surrealist of Polish-Jewish roots, in Czechoslovakia, where Vukotić and Švankmajer later worked on his Visitors from the Galaxy. Laloux, the author of several short animated films, would later make Gandahar (1987) with another comic author, Philippe Cazaumayoum Caza.

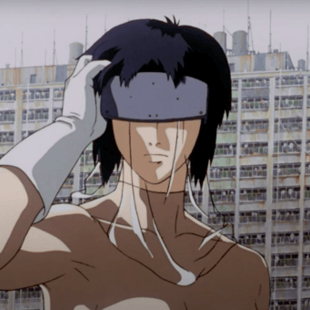

Nowhere, however, has the historical connection between animated film and science fiction been as strong as in Japan, the land of Gojira. The animated SF series Astro Boy (1963-66) by Osamu Tezuka, based on the master’s manga, became the origin of Japanese anime, whose most famous artist Hayao Miyazaki himself reached for speculative fiction. In the 1980s, feature-length animated film rose to the forefront of all cinematic science fiction thanks to Akira (1988) by Katsuhiro Ôtomo, who would deal intensively with the genre in his later works. It is a specific moment in the history of SF in which its film component simultaneously, and in some aspects even before the literary one, is included in the creation of the cyberpunk subgenre. Masamune Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell manga, adapted for the screen in 1995 by Mamoru Oshii, also originates from this period. The iconic film Ghost in the Shell, which will go on to have a decisive influence on later cyberpunk (e.g. The Matrix and its animated anthology sequel Animatrix), will be screened on Sunday 6/11 at the Tuškanac Summer Stage at 21:30 (“SF 7”).

Science fiction in the past of short animated film appears, however, sporadically and very rarely as a constant in some author’s oeuvre, or a permanent expression of a school or production company. The history of short-length animated SF has therefore not yet been thoroughly covered, so the theme programme of Animafest 2023 in nine units is structured topologically instead of chronologically. The position of sci-fi in short animation is also outlined to a certain extent in the production of Zagreb film, active on the border between East and West since the second half of the 1950s and has contributed to the animated revolution of global proportions – to the authors of the Zagreb School of science fiction, parables were only occasionally of socio-critical use. This ethos, however, will be updated again in the 21st century, so “SF 6” as a whole, dedicated to a selection of SF films from the 70-year history of Zagreb Film (Tuesday, June 6, SC Cinema, 10 p.m.), includes classics such as Vukotić’s Cow on the Moon and Grgić’s Visit from Space joined with the more recent works by Kukić (Vremeplov), Pisačić (Choban) and Belić (Flimflam).

The golden age of short animated science fiction is actually right now. In the last fifteen years, Animafest has presented dozens of excellent SFs in its competitions, among which we could single out those who are primarily interested in technology – both AI and other ‘software’ – and gather them into a unit “SF 1: The Future is Now” (Tuesday, June 6, &TD Theatre, 8 p.m. and Friday, June 9, SC Cinema, 3:30 p.m.). For example, Sean Buckelew, independently or as part of the collective Late Night Club, has appeared several times at the Zagreb festival since 2017 and the notable Lovestreams about encounters in virtual space, and his new film Drone, which is screened in this unit, is driven by the already established motif of the renegade spacecraft (cf. e.g. Vladislav Knežević’s A.D.A.M.). In the film Algodreams, Vladimir Todorović mentions AI software with which he willingly shares authorship, and Mitch McGlocklin’s pointillist-striped, neo-noir autobiographical etude in cyberspace Forever focuses on the topic of the relationship between advanced technology and human experience, that is, infamous algorithms that collect and analyse our private data. Realised in LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), Forever attributes to AI, however, the positive values of a guarantor of eternity and a companion in an alienated world. All My Scars Vanish in the Wind (dir. Angélica Restrepo, Carlos Velandia) uses photogrammetry, and the beautiful experimental Hysteresis by Robert Seidel, an artist particularly interested in nonlinear systems and bifurcations, also uses AI and digital compositing.

In “SF 2: The World of Tomorrow” (Thursday 6/8, &TD Theatre, 8 p.m. and Friday 6/9, Tuškanac, 5:30 p.m.) Trip to the Moon is also in the company of films less than a quarter of a century old. Among them are animation big names like Don Hertzfeldt’s eponymous World of Tomorrow – an Oscar-nominated Sundance winner and the starting point for a now three-part series that takes on a number of sci-fi tropes like cloning, time travel and melancholy, building an army of fans with a unique avant-garde-simple style and combination of humour and fatalism, philosophy and hope. There is also Phil Mulloy, a giant of satire and the grotesque, the prince of animanarchy and a fierce social critic who in his own way captures the war between Earth and the planet Zog (Intolerance II: The Invasion). Evert de Beijer’s Car Craze is also a work of raw animation – an environmental parable about parasitic body-stealing cars. Finally, Dmytro Lisenbart’s Ukrainian film of more classical beauty, Unnecessary Things, is based on Robert Sheckley’s short story about a near future where a lonely robot takes a human as a pet.

The contemporary flourishing of short SF does not mean, however, that some classic directors have not tried their hand at it. The recently deceased Belgian master, Animafest laureate Raoul Servais, did it back in 1971 with Operation X-70, an animation of copperplates telling the story of experimental nerve gas bombs, which will be screened in “SF 3: Disasters” (Thursday 6/8, Tuškanac, 5:30 p.m. and Friday 9 June, &TD Theatre, 8 p.m.). Operation X-70 is here put in context with more recent works of a similar theme, in which the modes of psychological SF and the motifs of astronauts prevail. Tomasz Popakul’s Black depicts them trapped on a space station in Earth’s orbit due to an atomic war, Marina Belikova’s The Astronaut’s Journal, based on Stanisław Lem, combines internal, introspective, humane and psychological research with the outer-spatial one, in the Turkish film Avarya by Gökalp Gönen a man is trapped with a robot on a spaceship in search of a habitable planet, and in 909 Depart of the Uber Eck studio we fly through the space station in first person and become aware of another end of the Earth. Kevin Iglesias Rodríguez and Pedro Rivero’s pandemic allegory The Days That (Never) Were is based on the premise of Jupiter occupying the Moon’s position, and Jérémy Clapin’s Skhizein is another psychological, highly original SF about a man that, due to a meteorite impact, experiences a “spatial shift” of 91 centimetres. It is the film that plastically points out the advantages of animated film in the presentation of “impossible” phenomena.

Chris Marker’s famous short photo-film SF La Jetée (1962) is less often mentioned in the context of an animated film, but the French New Wave artist made a stop-motion, collage-pixilation film Astronauts awarded in Venice and Oberhausen as early as 1959 with Walerian Borowczyk (whose birth centenary Animafest 2023 also marks in the Poland in Focus program). Astronauts are featured in “SF 4: Science Friction – Collage in Space” (Wednesday 6/7, &TD Theatre, 8pm and Friday 6/9, SC Cinema, 1pm) designed by Ottawa Festival Artistic Director Chris Robinson, naming it after the film Science Friction (1959) by the American legend of experimental stop animation Stan VanDerBeek, which, understandably, can also be seen in this block. It is interesting to note that the fruitful, albeit insufficiently thematised, historical triangle of experimental and animated film and science fiction, which is covered by this unit, has one of its most important contemporary expressions in the works of Dalibor Barić, undoubtedly the most important Croatian SF film author today, who designed the illustration and trailer of Animafest 2023. Dalibor Barić is represented in the unit “SF 4” by the found footage film Marienbad First Aid Kit (2013).

In the block “SF 4” you can also see the Hungarian Moon Flight (1975) by Sándor Reisenbüchler – a work from the famous Pannonia Film, a studio that once managed to realise the feature-length Moebius and Laloux’s The Masters of Time (1982) in addition to the works of Jankovics, Dargay and others. Along with newer films from Germany, Norway, Switzerland, Belgium and Hungary, the older Polish film Cockroach. Blatta orientalis by Zdzisława Kudła (1987) is shown in the block “SF 5: Speculative Animation – Return to the Post-Apocalypse” (Thursday 6/8, SC Cinema, 10 pm and Saturday 6/10, &TD Theatre, 8 p.m.) curated by the historian and animation theorist Olga Bobrowska. Science fiction creativity in Eastern Europe in the second half of the 20th century was exceptional, among other things, due to the fundamentally utopian foundations of the social system, but it is often glossed over in Western histories of the genre.

In Romania, Mircea Toia, Călin Cazan and Victor Antonescu also tried their hand at the feature form with ‘Delta’ Space Mission (1984), the restored version of which Animafest will show in “SF 9” (Tuškanac, Wednesday 6/7, 5:30 p.m.). It’s a film about an AI taking over a spaceship on an intergalactic mission, of episodic structure and seductive classic appearances. The Poles, in co-production with France, embarked on the feature SF with Chronopolis (1982) by Piotr Kamler (“SF 8”, Tuškanac, Tuesday 6 June, 17:30), which takes place in a city whose immortal inhabitants are freed from the boredom of eternal existence by devoting themselves to the production of time. A non-verbal spectacle of exceptional and inspiring stop-motion imagery achieved with complex materials and shadow, Chronopolis is a philosophical meditation on the nature of time. Kamler, who mostly worked alone in his avant-garde films, at the same time regularly collaborated with the most important electronic musicians of his time – on Chronopolis with Luca Ferrari.

Feature-length animated SF appeared in Western and Eastern Europe in the 1970s and 1980s, often in close connection with the tectonic shifts of art comics and the new wave of surrealism. Métal hurlant magazine will receive Gerald Potterton’s Heavy Metal (1981), and Moebius himself will collaborate with Rene Laloux on The Masters of Time in Hungary. Back in 1973, Laloux made perhaps the crucial feature-length animated SF Fantastic / Wild Planet with Roland Topor, a French surrealist of Polish-Jewish roots, in Czechoslovakia, where Vukotić and Švankmajer later worked on his Visitors from the Galaxy. Laloux, the author of several short animated films, would later make Gandahar (1987) with another comic author, Philippe Cazaumayoum Caza.

Nowhere, however, has the historical connection between animated film and science fiction been as strong as in Japan, the land of Gojira. The animated SF series Astro Boy (1963-66) by Osamu Tezuka, based on the master’s manga, became the origin of Japanese anime, whose most famous artist Hayao Miyazaki himself reached for speculative fiction. In the 1980s, feature-length animated film rose to the forefront of all cinematic science fiction thanks to Akira (1988) by Katsuhiro Ôtomo, who would deal intensively with the genre in his later works. It is a specific moment in the history of SF in which its film component simultaneously, and in some aspects even before the literary one, is included in the creation of the cyberpunk subgenre. Masamune Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell manga, adapted for the screen in 1995 by Mamoru Oshii, also originates from this period. The iconic film Ghost in the Shell, which will go on to have a decisive influence on later cyberpunk (e.g. The Matrix and its animated anthology sequel Animatrix), will be screened on Sunday 6/11 at the Tuškanac Summer Stage at 21:30 (“SF 7”).